Martyn McLaughlin

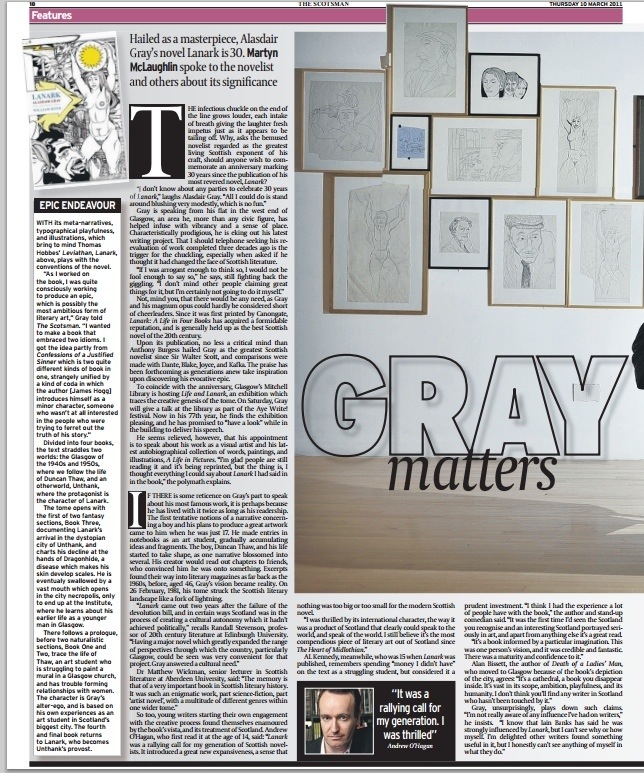

‘Gray Matters’ from The Scotsman. Interviews with Alasdair Gray and other leading writers on 30 years since Lanark.

THE infectious chuckle on the end of the line grows louder, each intake of breath giving the laughter fresh impetus just as it appears to be tailing off. Why, asks the bemused novelist regarded as the greatest living Scottish exponent of his craft, should anyone wish to commemorate an anniversary marking 30 years since the publication of his most revered novel, Lanark? “I don’t know about any parties to celebrate 30 years of Lanark,” laughs Alasdair Gray. “All I could do is stand around blushing very modestly, which is no fun.”

Gray is speaking from his flat in the west end of Glasgow, an area he, more than any civic figure, has helped infuse with vibrancy and a sense of place. Characteristically prodigious, he is eking out his latest writing project. That I should telephone seeking his re-evaluation of work completed three decades ago is the trigger for the chuckling, especially when asked if he thought it had changed the face of Scottish literature. “If I was arrogant enough to think so, I would not be fool enough to say so,” he says, still fighting back the giggling. “I don’t mind other people claiming great things for it, but I’m certainly not going to do it myself.”

Not, mind you, that there would be any need, as Gray and his magnum opus could hardly be considered short of cheerleaders. Since it was first printed by Canongate, Lanark: A Life in Four Books has acquired a formidable reputation, and is generally held up as the best Scottish novel of the 20th century. Upon its publication, no less a critical mind than Anthony Burgess hailed Gray as the greatest Scottish novelist since Sir Walter Scott, and comparisons were made with Dante, Blake, Joyce, and Kafka. The praise has been forthcoming as generations anew take inspiration upon discovering his evocative epic.

To coincide with the anniversary, Glasgow’s Mitchell Library is hosting Life and Lanark, an exhibition which traces the creative genesis of the tome. On Saturday, Gray will give a talk at the library as part of the Aye Write! festival. Now in his 77th year, he finds the exhibition pleasing, and he has promised to “have a look” while in the building to deliver his speech. He seems relieved, however, that his appointment is to speak about his work as a visual artist and his latest autobiographical collection of words, paintings, and illustrations, A Life in Pictures. “I’m glad people are still reading it and it’s being reprinted, but the thing is, I thought everything I could say about Lanark I had said in in the book,” the polymath explains.

If there is some reticence on Gray’s part to speak about his most famous work, it is perhaps because he has lived with it twice as long as his readership. The first tentative notions of a narrative concerning a boy and his plans to produce a great artwork came to him when he was just 17. He made entries in notebooks as an art student, gradually accumulating ideas and fragments. The boy, Duncan Thaw, and his life started to take shape, as one narrative blossomed into several. His creator would read out chapters to friends, who convinced him he was onto something. Excerpts found their way into literary magazines as far back as the 1960s, before, aged 46, Gray’s vision became reality. On 26 February, 1981, his tome struck the Scottish literary landscape like a fork of lightning.

“Lanark came out two years after the failure of the devolution bill, and in certain ways Scotland was in the process of creating a cultural autonomy which it hadn’t achieved politically,” recalls Randall Stevenson, professor of 20th century literature at Edinburgh University. “Having a major novel which greatly expanded the range of perspectives through which the country, particularly Glasgow, could be seen was very convenient for that project. Gray answered a cultural need.”

Dr Matthew Wickman, senior lecturer in Scottish literature at Aberdeen University, said: “The memory is that of a very important book in Scottish literary history. It was such an enigmatic work, part science-fiction, part ‘artist novel’, with a multitude of different genres within one wider tome.”

So too, young writers starting their own engagement with the creative process found themselves enamoured by the book’s vista, and its treatment of Scotland. Andrew O’Hagan, who first read it at the age of 14, said: “Lanark was a rallying call for my generation of Scottish novelists. It introduced a great new expansiveness, a sense that nothing was too big or too small for the modern Scottish novel. I was thrilled by its international character, the way it was a product of Scotland that clearly could speak to the world, and speak of the world. I still believe it’s the most compendious piece of literary art out of Scotland since The Heart of Midlothian.”

AL Kennedy, meanwhile, who was 15 when Lanark was published, remembers spending “money I didn’t have” on the text as a struggling student, but considered it a prudent investment. “I think I had the experience a lot of people have with the book,” the author and stand-up comedian said. “It was the first time I’d seen the Scotland you recognise and an interesting Scotland portrayed seriously in art, and apart from anything else it’s a great read. It’s a book informed by a particular imagination. This was one person’s vision, and it was credible and fantastic. There was a maturity and confidence to it.”

Alan Bissett, the author of Death of a Ladies’ Man, who moved to Glasgow because of the book’s depiction of the city, agrees: “It’s a cathedral, a book you disappear inside. It’s vast in its scope, ambition, playfulness, and its humanity. I don’t think you’ll find any writer in Scotland who hasn’t been touched by it.”

Gray, unsurprisingly, plays down such claims. “I’m not really aware of any influence I’ve had on writers,” he insists. “I know that Iain Banks has said he was strongly influenced by Lanark, but I can’t see why or how myself. I’m delighted other writers found something useful in it, but I honestly can’t see anything of myself in what they do.”

For all the confidence Lanark gave to young Scots writers, with Gray showing that a Scottish book can be a thing of wild-eyed imagination, some urge caution when seeking to assess its wider appeal. Historian Professor Tom Devine, regards Gray’s work as one of several modern Scottish books which has helped change the way artists view the country, but believes that crucially, its literary style has prevented it becoming more widely read.

He said: “The question about the impact of Lanark reminds me of the impact of Hugh MacDiarmid in the 1920s and 1930s, when his poetry was praised but the knowledge of that poetry was limited to an arcane circle. That was partly because it was difficult, and I honestly do think Lanark is also difficult and challenging. I would say is that its impact must be regarded, at least among the majority of Scots, as minimal. This is a point which literary commentators rarely make.”

Dr Eleanor Bell, who teaches the book at Strathclyde University, regards it as “the most important Scottish novel of the 20th century,” but she believes its popularity is limited to certain circles. “It’s a novel which tends to be taught at university,” she said. “I would say most Scots wouldn’t have read Lanark and wouldn’t necessarily go about reading it. It goes back to Scottish literature not being promoted as well as it could be in schools, and so it’s not something people are drawn to read.”

Others, though, believe Gray’s work has played a more important role in bringing Scottish literature to a greater international audience. Professor Willy Maley, of the department of English literature at Glasgow University, who helped found the creative writing course on which Gray taught, said: “Whenever I’ve travelled around the world and taught Alasdair’s work, I’m astonished at the reach of Lanark and the impact it had. I’ve talked about him in Santiago and Cleveland and they get him. The book was a profound literary landmark.” Stevenson agrees: “It’s one of the books which helped Scottish writing to be read and admired outside the country.”

For all that, even Gray’s admirers believe the 30th anniversary offers reason to remind the world of his talents. “The book has an international reputation but it hasn’t spread as far as it should,” argues Bissett, who said Gray was “unknown” to people when he taught creative writing at Leeds University a few years back. “It isn’t talked about it as much as it should be, but I think if was it set in London or New York, it would be discussed in the same breath as Bonfire of the Vanities. But because it’s set in Scotland, it limits its prestige – exactly the sort of thing the book is trying to regress.”

Discussion

No comments yet.